The Gestalt therapeutic encounter

It is important that the person working as a psychotherapist has as high a level of awareness as possible. This is one of the reasons why it is good that he or she has had their own personal therapy for a sufficient amount of time before embarking on the road to becoming a psychotherapist. It should also be a matter of course that he or she, henceforth, during the time of education and particularly when starting to practice as a therapist, at least periodically attends counseling and personal psychotherapy. A therapist is, as broached in Article 1, his or her own best tool and not taking sufficient care of one’s tools can be quite dangerous.

Counseling and personal psychotherapy are not identical

Counseling and personal psychotherapy are not the same thing. It is good for a therapist, or any employee for that matter, to make use of both, and it is important that he or she personally makes a distinction between them. He or she should be aware of what themes belong to work and therefore should be attended to in counseling, and which belong to him- or herself and should therefore be attended to in personal psychotherapy.

Encounter instead of interpretation

The Gestalt therapist is simultaneously approachable and distanced in the relations with the client. She remains vigilant, expectant, and respectful regardless of what problems the client brings into therapy. The therapist alertly utilizes intuition and intellect continuously during a therapy session. The therapist is also able to register his or her own personal reactions to what the client does and says, and the therapist should remain constantly able to estimate which of these reactions are relevant to share with the client and which to keep to him- or herself because they are not relevant or hold no value for the therapeutic process. The therapist must also be attentive to that the client and the therapist do not automatically hold the same view of reality or frames of reference. The therapist observes the client and continually strives to find out what everything means to the client, instead of presupposing an “understanding”. This understanding signifying then the therapist noticing his or her own associations and thereby interpreting what the client has said and done. If this happens, the therapist loses touch with the client and is instead in contact with his or her own fantasies about the client.

The point of departure for the cooperation

Gestalt therapy only works if a cooperation and contact is established between the therapist and client. Therefore, it is important that the therapist as soon as possible makes out how this cooperation should be sustained. The gestalt therapeutic diagnosis should therefore be set early on in the therapeutic cooperation, and then be adjusted continuously after that. The diagnosis stems from the therapist’s hypothesis about and experience of the client’s contact ability and will be continuously based on the client’s behavior here and now. It is up to the therapist how much and in what way he or she wants to inform the client of his or her experiences of what the client assimilates or rejects in the contact encounter. This will be due to the therapist’s evaluation of if the information will strengthen the client’s readiness for increased contact, or if it only hurts the client in the situation. For instance, in a way that the client feels to be to forcefully confronted and therefore pulls back from more contact.

Moving out of contact

The Danish psychologist and Gestalt therapist Hanne Hostrup says in one of her works that when a therapist knows the diagnosis he or she should act in such a way so the client has the best chance to not experience being offended. injured, indifferent, dependent, subservient, ignored, or in any other way feel the need to end the cooperation by moving out of contact. One of the purposes with the diagnosis is that both client and therapist should be aware of the client’s usual way to move out of cooperation or collaboration. This makes the client able to consciously choose if he or she wants to continue using this pattern to move out of contact or alternatively to change it.

It is clear that I, in the meeting with a new client, create certain perceptions of the client, his or her issues and basic personality. But, since diagnosis to me is a changeable and variable factor constantly arising again and again in every moment of cooperation with a client, I try to be conscious of that the diagnosis of last week, last month or last minute should not affect the diagnosis of the current moment. In all due respect for how others make their diagnoses on the same client, I try not to let these diagnoses come in the way of my work with the client. I gladly hold these at the back of my head as hypotheses and test their probability during sessions, but they are not allowed to get the upper hand of and dominate my interplay with and my experience of the client here and now.

This article is the ninth in a series of twelve articles on the concept of psychotherapy and the use of psychotherapeutic methods. The following article will deal with practicing the arts as a contrast to art therapy.

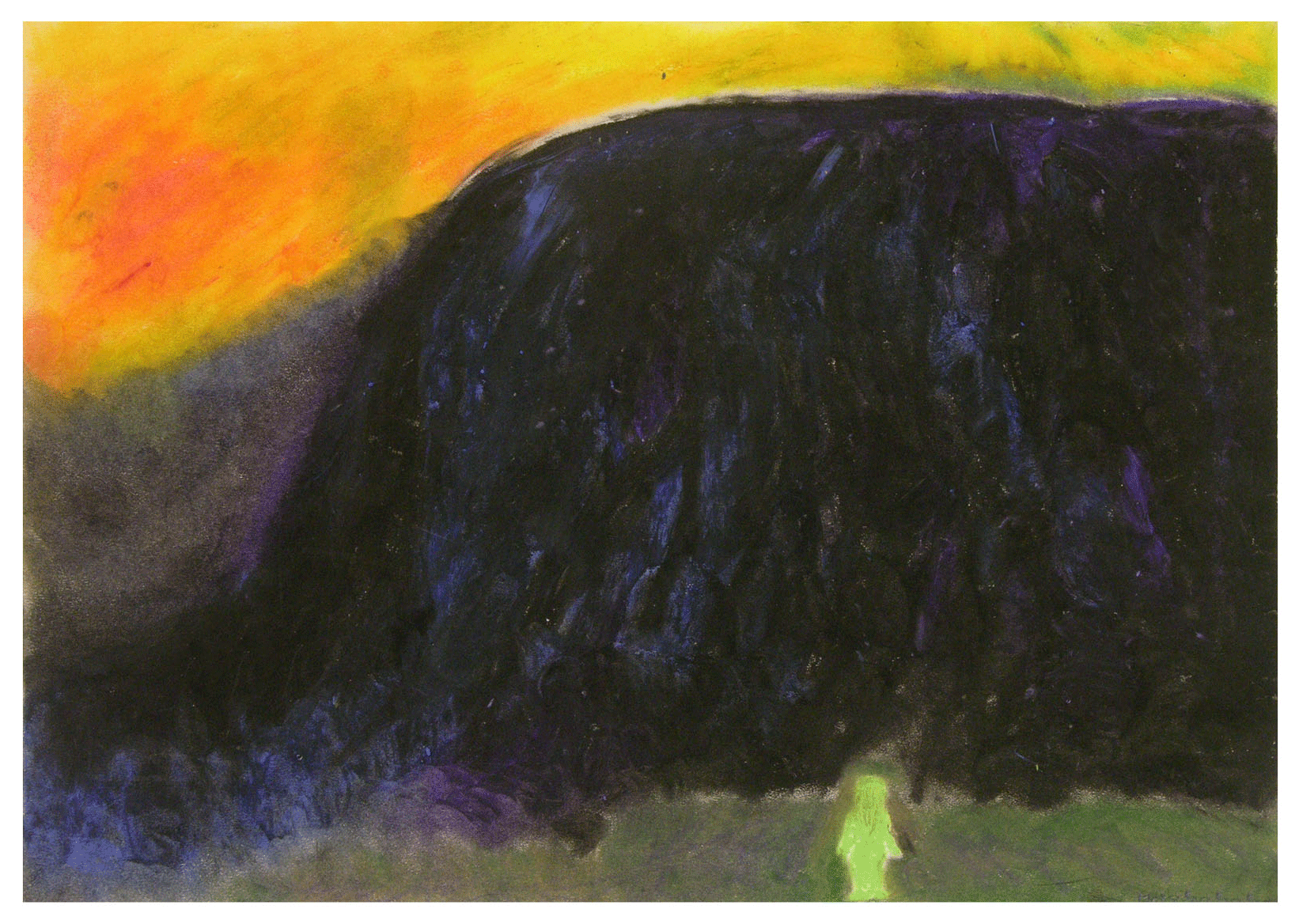

Text and illustrations: Tine Sylvest

Photographs: Bo Mellberg

The author is a certified Psychotherapist, Art Therapist and Workplace Counselor/Coach born in Denmark, currently living and practicing in the Swedish-speaking parts of Finland.

Next page : Art therapy – another way of thinking